Urbino University

| University of Urbino "Carlo Bo" | |

|---|---|

| Università degli Studi di Urbino "Carlo Bo" | |

| |

| Established | 1506 |

| Type | State-supported |

| Rector | Prof. Stefano Pivato |

| Students | 22,000 |

| Location | Urbino, Italy |

| Website | www.uniurb.it |

The University of Urbino "Carlo Bo" (Italian: Università degli Studi di Urbino "Carlo Bo", UNIURB) is an Italian university located in Urbino, a walled hill-town in the region of Marche, located in the north-eastern part of central Italy. The university was founded in 1506, and currently has about 20,000 students, many of whom are from overseas. The university has no central campus as such, and instead occupies numerous buildings throughout the town and in the surrounding countryside. The main accommodation blocks are situated a short distance from the town.

The University of Urbino has traditionally given precedence to studies in the humanities, and is especially renowned for its courses in Italian language. In recent years it has suffered economic difficulties, and is currently in the process of becoming state-owned.

Organization

The University is divided into 11 faculties:

- Faculty of Economics

Economics is the social science that analyzes the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services. The term economics comes from the Ancient Greek οἰκονομία (oikonomia, "management of a household, administration") from οἶκος (oikos, "house") + νόμος (nomos, "custom" or "law"), hence "rules of the house(hold)". Political economy was the earlier name for the subject, but economists in the latter 19th century suggested 'economics' as a shorter term for 'economic science' that also avoided a narrow political-interest connotation and as similar in form to 'mathematics', 'ethics', and so forth.

A focus of the subject is how economic agents behave or interact and how economies work. Consistent with this, a primary textbook distinction is between microeconomics and macroeconomics. Microeconomics examines the behavior of basic elements in the economy, including individual agents (such as households and firms or as buyers and sellers) and markets, and their interactions. Macroeconomics analyzes the entire economy and issues affecting it, including unemployment, inflation, economic growth, and monetary and fiscal policy.

Other broad distinctions include those between positive economics (describing "what is") and normative economics (advocating "what ought to be"); between economic theory and applied economics; between rational and behavioral economics; and between mainstream economics (more "orthodox" dealing with the "rationality-individualism-equilibrium nexus") and heterodox economics (more "radical" dealing with the "institutions-history-social structure nexus").

Economic analysis may be applied throughout society, as in business, finance, health care, and government, but also to such diverse subjects as crime, education, the family, law, politics, religion, social institutions, war, and science. At the turn of the 21st century, the expanding domain of economics in the social sciences has been described as economic imperialism.

Modern definitions of the subject

There are a variety of modern definitions of economics. Some of the differences may reflect evolving views of the subject or different views among economists. The philosopher Adam Smith (1776) defined what was then called political economy as "an inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations", in particular as:

- a branch of the science of a statesman or legislator [with the twofold objectives of providing] a plentiful revenue or subsistence for the people ... [and] to supply the state or commonwealth with a revenue for the publick services.

J.-B. Say (1803), distinguishing the subject from its public-policy uses, defines it as the science of production, distribution, and consumption of wealth. On the satirical side, Thomas Carlyle (1849) coined 'the dismal science' as an epithet for classical economics, in this context, commonly linked to the pessimistic analysis of Malthus (1798). John Stuart Mill (1844) defines the subject in a social context as:

- The science which traces the laws of such of the phenomena of society as arise from the combined operations of mankind for the production of wealth, in so far as those phenomena are not modified by the pursuit of any other object.

Alfred Marshall provides a still widely-cited definition in his textbook Principles of Economics (1890) that extends analysis beyond wealth and from the societal to the microeconomic level:

- Economics is a study of man in the ordinary business of life. It enquires how he gets his income and how he uses it. Thus, it is on the one side, the study of wealth and on the other and more important side, a part of the study of man.

Lionel Robbins (1932) developed implications of what has been termed "[p]erhaps the most commonly accepted current definition of the subject":

- Economics is a science which studies human behaviour as a relationship between ends and scarce means which have alternative uses.

Robbins describes the definition as not classificatory in "pick[ing] out certain kinds of behaviour" but rather analytical in "focus[ing] attention on a particular aspect of behaviour, the form imposed by the influence of scarcity."

Some subsequent comments criticized the definition as overly broad in failing to limit its subject matter to analysis of markets. From the 1960s, however, such comments abated as the economic theory of maximizing behavior and rational-choice modeling expanded the domain of the subject to areas previously treated in other fields. There are other criticisms as well, such as in scarcity not accounting for the macroeconomics of high unemployment.

Gary Becker, a contributor to the expansion of economics into new areas, describes the approach he favors as "combin[ing the] assumptions of maximizing behavior, stable preferences, and market equilibrium, used relentlessly and unflinchingly." One commentary characterizes the remark as making economics an approach rather than a subject matter but with great specificity as to the "choice process and the type of social interaction that [such] analysis involves." The same source reviews a range of definitions included in principles of economics textbooks and concludes that the lack of agreement need not affect the subject-matter that the texts treat. Among economists more generally, it argues that a particular definition presented may reflect the direction toward which the author believes economics is evolving, or should evolve.

Supply and demand

Prices and quantities have been described as the most directly observable attributes of goods produced and exchanged in a market economy. The theory of supply and demand is an organizing principle for explaining how prices coordinate the amounts produced and consumed. In microeconomics, it applies to price and output determination for a market with perfect competition, which includes the condition of no buyers or sellers large enough to have price-setting power.

For a given market of a commodity, demand is the relation of the quantity that all buyers would be prepared to purchase at each unit price of the good. Demand is often represented by a table or a graph showing price and quantity demanded (as in the figure). Demand theory describes individual consumers as rationally choosing the most preferred quantity of each good, given income, prices, tastes, etc. A term for this is 'constrained utility maximization' (with income and wealth as the constraints on demand). Here, utility refers to the hypothesized relation of each individual consumer for ranking different commodity bundles as more or less preferred.

The law of demand states that, in general, price and quantity demanded in a given market are inversely related. That is, the higher the price of a product, the less of it people would be prepared to buy of it (other things unchanged). As the price of a commodity falls, consumers move toward it from relatively more expensive goods (the substitution effect). In addition, purchasing power from the price decline increases ability to buy (the income effect). Other factors can change demand; for example an increase in income will shift the demand curve for a normal good outward relative to the origin, as in the figure. All determinants are predominantly taken as constant factors of demand and supply.

Supply is the relation between the price of a good and the quantity available for sale at that price. It may be represented as a table or graph relating price and quantity supplied. Producers, for example business firms, are hypothesized to be profit-maximizers, meaning that they attempt to produce and supply the amount of goods that will bring them the highest profit. Supply is typically represented as a directly-proportional relation between price and quantity supplied (other things unchanged). That is, the higher the price at which the good can be sold, the more of it producers will supply, as in the figure. The higher price makes it profitable to increase production. Just as on the demand side, the position of the supply can shift, say from a change in the price of a productive input or a technical improvement. The "Law of Supply" states that, in general, a rise in price leads to an expansion in supply and a fall in price leads to a contraction in supply. Here as well, the determinants of supply, such as price of substitutes, cost of production, technology applied and various factors inputs of production are all taken to be constant for a specific time period of evaluation of supply.

Market equilibrium occurs where quantity supplied equals quantity demanded, the intersection of the supply and demand curves in the figure above. At a price below equilibrium, there is a shortage of quantity supplied compared to quantity demanded. This is posited to bid the price up. At a price above equilibrium, there is a surplus of quantity supplied compared to quantity demanded. This pushes the price down. The model of supply and demand predicts that for given supply and demand curves, price and quantity will stabilize at the price that makes quantity supplied equal to quantity demanded. Similarly, demand-and-supply theory predicts a new price-quantity combination from a shift in demand (as to the figure), or in supply.

For a given quantity of a consumer good, the point on the demand curve indicates the value, or marginal utility, to consumers for that unit. It measures what the consumer would be prepared to pay for that unit.

The corresponding point on the supply curve measures marginal cost, the increase in total cost to the supplier for the corresponding unit of the good. The price in equilibrium is determined by supply and demand. In a perfectly competitive market, supply and demand equate marginal cost and marginal utility at equilibrium.

On the supply side of the market, some factors of production are described as (relatively) variable in the short run, which affects the cost of changing output levels. Their usage rates can be changed easily, such as electrical power, raw-material inputs, and over-time and temp work. Other inputs are relatively fixed, such as plant and equipment and key personnel. In the long run, all inputs may be adjusted by management. These distinctions translate to differences in the elasticity (responsiveness) of the supply curve in the short and long runs and corresponding differences in the price-quantity change from a shift on the supply or demand side of the market.

Marginalist theory, such as above, describes the consumers as attempting to reach most-preferred positions, subject to income and wealth constraints while producers attempt to maximize profits subject to their own constraints, including demand for goods produced, technology, and the price of inputs. For the consumer, that point comes where marginal utility of a good, net of price, reaches zero, leaving no net gain from further consumption increases. Analogously, the producer compares marginal revenue (identical to price for the perfect competitor) against the marginal cost of a good, with marginal profit the difference. At the point where marginal profit reaches zero, further increases in production of the good stop. For movement to market equilibrium and for changes in equilibrium, price and quantity also change "at the margin": more-or-less of something, rather than necessarily all-or-nothing.

Other applications of demand and supply include the distribution of income among the factors of production, including labour and capital, through factor markets. In a competitive labour market for example the quantity of labour employed and the price of labour (the wage rate) depends on the demand for labour (from employers for production) and supply of labour (from potential workers). Labour economics examines the interaction of workers and employers through such markets to explain patterns and changes of wages and other labour income, labour mobility, and (un)employment, productivity through human capital, and related public-policy issues.

Demand-and-supply analysis is used to explain the behavior of perfectly competitive markets, but as a standard of comparison it can be extended to any type of market. It can also be generalized to explain variables across the economy, for example, total output (estimated as real GDP) and the general price level, as studied in macroeconomics. Tracing the qualitative and quantitative effects of variables that change supply and demand, whether in the short or long run, is a standard exercise in applied economics. Economic theory may also specify conditions such that supply and demand through the market is an efficient mechanism for allocating resources.- Faculty of Education

Education in its broadest, general sense is the means through which the aims and habits of a group of people lives on from one generation to the next. Generally, it occurs through any experience that has a formative effect on the way one thinks, feels, or acts. In its narrow, technical sense, education is the formal process by which society deliberately transmits its accumulated knowledge, skills, customs and values from one generation to another, e.g., instruction in schools.

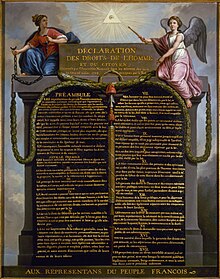

A right to education has been created and recognized by some jurisdictions: Since 1952, Article 2 of the first Protocol to the European Convention on Human Rights obliges all signatory parties to guarantee the right to education. At the global level, the United Nations' International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights of 1966 guarantees this right under its Article 13.

Systems of higher education

The University of Cambridge is an institute of higher learning.

Higher education, also called tertiary, third stage, or post secondary education, is the non-compulsory educational level that follows the completion of a school providing a secondary education, such as a high school or secondary school. Tertiary education is normally taken to include undergraduate and postgraduate education, as well as vocational education and training. Colleges and universities are the main institutions that provide tertiary education. Collectively, these are sometimes known as tertiary institutions. Tertiary education generally results in the receipt of certificates, diplomas, or academic degrees.

Higher education generally involves work towards a degree-level or foundation degree qualification. In most developed countries a high proportion of the population (up to 50%) now enter higher education at some time in their lives. Higher education is therefore very important to national economies, both as a significant industry in its own right, and as a source of trained and educated personnel for the rest of the economy.

University systems

University education includes teaching, research and social services activities, and it includes both the undergraduate level (sometimes referred to as tertiary education) and the graduate (or postgraduate) level (sometimes referred to as graduate school). Universities are generally composed of several colleges. In the United States, universities can be private and independent, like Yale University, they can be public and State governed, like the Pennsylvania State System of Higher Education, or they can be independent but State funded, like the University of Virginia.

- Faculty of Environmental Sciences

Environmental science is an interdisciplinary academic field that integrates physical and biological sciences, (including but not limited to Ecology, Physics, Chemistry, Biology, Soil Science, Geology, Atmospheric Science and Geography) to the study of the environment, and the solution of environmental problems. Environmental science provides an integrated, quantitative, and interdisciplinary approach to the study of environmental systems.

Related areas of study include environmental studies and environmental engineering. Environmental studies incorporates more of the social sciences for understanding human relationships, perceptions and policies towards the environment. Environmental engineering focuses on design and technology for improving environmental quality.

Environmental scientists work on subjects like the understanding of earth processes, evaluating alternative energy systems, pollution control and mitigation, natural resource management, and the effects of global climate change. Environmental issues almost always include an interaction of physical, chemical, and biological processes. Environmental scientists bring a systems approach to the analysis of environmental problems. Key elements of an effective environmental scientist include the ability to relate space, and time relationships as well as quantitative analysis.

Environmental science came alive as a substantive, active field of scientific investigation in the 1960s and 1970s driven by (a) the need for a multi-disciplinary approach to analyze complex environmental problems, (b) the arrival of substantive environmental laws requiring specific environmental protocols of investigation and (c) the growing public awareness of a need for action in addressing environmental problems. Events that spurred this development included the publication of Rachael Carson's landmark environmental book Silent Spring along with major environmental issues becoming very public, such as the 1969 Santa Barbara oil spill, and the Cuyahoga River of Cleveland, Ohio, "catching fire" (also in 1969), and helped increase the visibility of environmental issues and create this new field of study.

Regulations driving the studies

Environmental science examines the effects of humans on nature (Glen Canyon Dam in the U.S.)

In the U.S. the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) of 1969 set forth requirements for analysis of major projects in terms of specific environmental criteria. Numerous state laws have echoed these mandates, applying the principles to local-scale actions. The upshot has been an explosion of documentation and study of environmental consequences before the fact of development actions.

One can examine the specifics of environmental science by reading examples of Environmental Impact Statements prepared under NEPA such as: Wastewater treatment expansion options discharging into the San Diego/Tijuana Estuary, Expansion of the San Francisco International Airport, Development of the Houston, Metro Transportation system, Expansion of the metropolitan Boston MBTA transit system, and Construction of Interstate 66 through Arlington, Virginia.

In England and Wales the Environment Agency (EA), formed in 1996, is a public body for protecting and improving the environment and enforces the regulations listed on the communities and local government site. (formerly the office of the deputy prime minister). The agency was set up under the Environment Act 1995 as an independent body and works closely with UK Government to enforce the regulations.

Terminology

In common usage, "environmental science" and "ecology" are often used interchangeably, but technically, ecology refers only to the study of organisms and their interactions with each other and their environment. Ecology could be considered a subset of environmental science, which also could involve purely chemical or public health issues (for example) ecologists would be unlikely to study. In practice, there is considerable overlap between the work of ecologists and other environmental scientists.

The National Center for Education Statistics in the United States defines an academic program in environmental science as follows:

A program that focuses on the application of biological, chemical, and physical principles to the study of the physical environment and the solution of environmental problems, including subjects such as abating or controlling environmental pollution and degradation; the interaction between human society and the natural environment; and natural resources management. Includes instruction in biology, chemistry, physics, geosciences, climatology, statistics, and mathematical modeling.

- Faculty of Law

Law is a system of rules and guidelines which are enforced through social institutions to govern behavior, wherever possible. It shapes politics, economics and society in numerous ways and serves as a social mediator of relations between people. Contract law regulates everything from buying a bus ticket to trading on derivatives markets. Property law defines rights and obligations related to the transfer and title of personal and real property. Trust law applies to assets held for investment and financial security, while tort law allows claims for compensation if a person's rights or property are harmed. If the harm is criminalised in legislation, criminal law offers means by which the state can prosecute the perpetrator. Constitutional law provides a framework for the creation of law, the protection of human rights and the election of political representatives. Administrative law is used to review the decisions of government agencies, while international law governs affairs between sovereign states in activities ranging from trade to environmental regulation or military action. Writing in 350 BC, the Greek philosopher Aristotle declared, "The rule of law is better than the rule of any individual."

Legal systems elaborate rights and responsibilities in a variety of ways. A general distinction can be made between civil law jurisdictions, which codify their laws, and common law systems, where judge made law is not consolidated. In some countries, religion informs the law. Law provides a rich source of scholarly inquiry, into legal history, philosophy, economic analysis or sociology. Law also raises important and complex issues concerning equality, fairness and justice. "In its majestic equality", said the author Anatole France in 1894, "the law forbids rich and poor alike to sleep under bridges, beg in the streets and steal loaves of bread."

In a typical democracy, the central institutions for interpreting and creating law are the three main branches of government, namely an impartial judiciary, a democratic legislature, and an accountable executive. To implement and enforce the law and provide services to the public, a government's bureaucracy, the military and police are vital. While all these organs of the state are creatures created and bound by law, an independent legal profession and a vibrant civil society inform and support their progress.

Legal subjects

All legal systems deal with the same basic issues, but jurisdictions categorise and identify its legal subjects in different ways. A common distinction is that between "public law" (a term related closely to the state, and including constitutional, administrative and criminal law), and "private law" (which covers contract, tort and property). In civil law systems, contract and tort fall under a general law of obligations, while trusts law is dealt with under statutory regimes or international conventions. International, constitutional and administrative law, criminal law, contract, tort, property law and trusts are regarded as the "traditional core subjects", although there are many further disciplines .

International law

International law can refer to three things: public international law, private international law or conflict of laws and the law of supranational organisations.

- Public international law concerns relationships between sovereign nations. The sources for public international law development are custom, practice and treaties between sovereign nations, such as the Geneva Conventions. Public international law can be formed by international organisations, such as the United Nations (which was established after the failure of the League of Nations to prevent the Second World War), the International Labour Organisation, the World Trade Organisation, or the International Monetary Fund. Public international law has a special status as law because there is no international police force, and courts (e.g. the International Court of Justice as the primary UN judicial organ) lack the capacity to penalise disobedience. However, a few bodies, such as the WTO, have effective systems of binding arbitration and dispute resolution backed up by trade sanctions.

- Conflict of laws (or "private international law" in civil law countries) concerns which jurisdiction a legal dispute between private parties should be heard in and which jurisdiction's law should be applied. Today, businesses are increasingly capable of shifting capital and labour supply chains across borders, as well as trading with overseas businesses, making the question of which country has jurisdiction even more pressing. Increasing numbers of businesses opt for commercial arbitration under the New York Convention 1958.

- European Union law is the first and, so far, only example of a supranational legal framework. Given the trend of increasing global economic integration, many regional agreements—especially the Union of South American Nations—are on track to follow the same model. In the EU, sovereign nations have gathered their authority in a system of courts and political institutions. These institutions are allowed the ability to enforce legal norms both against or for member states and citizens in a manner which is not possible through public international law. As the European Court of Justice said in the 1960s, European Union law constitutes "a new legal order of international law" for the mutual social and economic benefit of the member states.

Constitutional and administrative law

Constitutional and administrative law govern the affairs of the state. Constitutional law concerns both the relationships between the executive, legislature and judiciary and the human rights or civil liberties of individuals against the state. Most jurisdictions, like the United States and France, have a single codified constitution with a bill of rights. A few, like the United Kingdom, have no such document. A "constitution" is simply those laws which constitute the body politic, from statute, case law and convention. A case named Entick v Carrington illustrates a constitutional principle deriving from the common law. Mr Entick's house was searched and ransacked by Sheriff Carrington. When Mr Entick complained in court, Sheriff Carrington argued that a warrant from a Government minister, the Earl of Halifax, was valid authority. However, there was no written statutory provision or court authority. The leading judge, Lord Camden, stated that,

The great end, for which men entered into society, was to secure their property. That right is preserved sacred and incommunicable in all instances, where it has not been taken away or abridged by some public law for the good of the whole ... If no excuse can be found or produced, the silence of the books is an authority against the defendant, and the plaintiff must have judgment.

The fundamental constitutional principle, inspired by John Locke, holds that the individual can do anything but that which is forbidden by law, and the state may do nothing but that which is authorised by law.

Administrative law is the chief method for people to hold state bodies to account. People can apply for judicial review of actions or decisions by local councils, public services or government ministries, to ensure that they comply with the law. The first specialist administrative court was the Conseil d'État set up in 1799, as Napoleon assumed power in France.

Criminal law

Criminal law, also known as penal law, pertains to crimes and punishment. It thus regulates the definition of and penalties for offences found to have a sufficiently deleterious social impact but, in itself, makes no moral judgment on an offender nor imposes restrictions on society that physically prevents people from committing a crime in the first place. Investigating, apprehending, charging, and trying suspected offenders is regulated by the law of criminal procedure. The paradigm case of a crime lies in the proof, beyond reasonable doubt, that a person is guilty of two things. First, the accused must commit an act which is deemed by society to be criminal, or actus reus (guilty act). Second, the accused must have the requisite malicious intent to do a criminal act, or mens rea (guilty mind). However for so called "strict liability" crimes, an actus reus is enough. Criminal systems of the civil law tradition distinguish between intention in the broad sense (dolus directus and dolus eventualis), and negligence. Negligence does not carry criminal responsibility unless a particular crime provides for its punishment.

Examples of crimes include murder, assault, fraud and theft. In exceptional circumstances defences can apply to specific acts, such as killing in self defence, or pleading insanity. Another example is in the 19th century English case of R v Dudley and Stephens, which tested a defence of "necessity". The Mignonette, sailing from Southampton to Sydney, sank. Three crew members and Richard Parker, a 17 year old cabin boy, were stranded on a raft. They were starving and the cabin boy was close to death. Driven to extreme hunger, the crew killed and ate the cabin boy. The crew survived and were rescued, but put on trial for murder. They argued it was necessary to kill the cabin boy to preserve their own lives. Lord Coleridge, expressing immense disapproval, ruled, "to preserve one's life is generally speaking a duty, but it may be the plainest and the highest duty to sacrifice it." The men were sentenced to hang, but public opinion was overwhelmingly supportive of the crew's right to preserve their own lives. In the end, the Crown commuted their sentences to six months in jail.

Criminal law offences are viewed as offences against not just individual victims, but the community as well. The state, usually with the help of police, takes the lead in prosecution, which is why in common law countries cases are cited as "The People v ..." or "R (for Rex or Regina) v ..." Also, lay juries are often used to determine the guilt of defendants on points of fact: juries cannot change legal rules. Some developed countries still condone capital punishment for criminal activity, but the normal punishment for a crime will be imprisonment, fines, state supervision (such as probation), or community service. Modern criminal law has been affected considerably by the social sciences, especially with respect to sentencing, legal research, legislation, and rehabilitation. On the international field, 111 countries are members of the International Criminal Court, which was established to try people for crimes against humanity.

Contract law

Contract law concerns enforceable promises, and can be summed up in the Latin phrase pacta sunt servanda (agreements must be kept). In common law jurisdictions, three key elements to the creation of a contract are necessary: offer and acceptance, consideration and the intention to create legal relations. In Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Company a medical firm advertised that its new wonder drug, the smokeball, would cure people's flu, and if it did not, the buyers would get £100. Many people sued for their £100 when the drug did not work. Fearing bankruptcy, Carbolic argued the advert was not to be taken as a serious, legally binding offer. It was an invitation to treat, mere puff, a gimmick. But the court of appeal held that to a reasonable man Carbolic had made a serious offer. People had given good consideration for it by going to the "distinct inconvenience" of using a faulty product. "Read the advertisement how you will, and twist it about as you will", said Lord Justice Lindley, "here is a distinct promise expressed in language which is perfectly unmistakable".

"Consideration" indicates the fact that all parties to a contract have exchanged something of value. Some common law systems, including Australia, are moving away from the idea of consideration as a requirement. The idea of estoppel or culpa in contrahendo, can be used to create obligations during pre-contractual negotiations. In civil law jurisdictions, consideration is not required for a contract to be bindin. In France, an ordinary contract is said to form simply on the basis of a "meeting of the minds" or a "concurrence of wills". Germany has a special approach to contracts, which ties into property law. Their 'abstraction principle' (Abstraktionsprinzip) means that the personal obligation of contract forms separately from the title of property being conferred. When contracts are invalidated for some reason (e.g. a car buyer is so drunk that he lacks legal capacity to contract) the contractual obligation to pay can be invalidated separately from the proprietary title of the car. Unjust enrichment law, rather than contract law, is then used to restore title to the rightful owner.

Tort law

Torts, sometimes called delicts, are civil wrongs. To have acted tortiously, one must have breached a duty to another person, or infringed some pre-existing legal right. A simple example might be accidentally hitting someone with a cricket ball.Under the law of negligence, the most common form of tort, the injured party could potentially claim compensation for his injuries from the party responsible. The principles of negligence are illustrated by Donoghue v Stevenson. A friend of Mrs Donoghue ordered an opaque bottle of ginger beer (intended for the consumption of Mrs Donoghue) in a café in Paisley. Having consumed half of it, Mrs Donoghue poured the remainder into a tumbler. The decomposing remains of a snail floated out. She claimed to have suffered from shock, fell ill with gastroenteritis and sued the manufacturer for carelessly allowing the drink to be contaminated. The House of Lords decided that the manufacturer was liable for Mrs Donoghue's illness. Lord Atkin took a distinctly moral approach, and said,

The liability for negligence ... is no doubt based upon a general public sentiment of moral wrongdoing for which the offender must pay ... The rule that you are to love your neighbour becomes in law, you must not injure your neighbour; and the lawyer's question, Who is my neighbour? receives a restricted reply. You must take reasonable care to avoid acts or omissions which you can reasonably foresee would be likely to injure your neighbour.

This became the basis for the four principles of negligence; (1) Mr Stevenson owed Mrs Donoghue a duty of care to provide safe drinks (2) he breached his duty of care (3) the harm would not have occurred but for his breach and (4) his act was the proximate cause, or not too remote a consequence, of her harm. Another example of tort might be a neighbour making excessively loud noises with machinery on his property.

Under a nuisance claim the noise could be stopped. Torts can also involve intentional acts, such as assault, battery or trespass. A better known tort is defamation, which occurs, for example, when a newspaper makes unsupportable allegations that damage a politician's reputation. More infamous are economic torts, which form the basis of labour law in some countries by making trade unions liable for strikes, when statute does not provide immunity.

Property law

Property law governs valuable things that people call 'theirs'. Real property, sometimes called 'real estate' refers to ownership of land and things attached to it. Personal property, refers to everything else; movable objects, such as computers, cars, jewelry, and sandwiches, or intangible rights, such as stocks and shares. A right in rem is a right to a specific piece of property, contrasting to a right in personam which allows compensation for a loss, but not a particular thing back. Land law forms the basis for most kinds of property law, and is the most complex. It concerns mortgages, rental agreements, licences, covenants, easements and the statutory systems for land registration. Regulations on the use of personal property fall under intellectual property, company law, trusts and commercial law. An example of a basic case of most property law is Armory v Delamirie. A chimney sweep's boy found a jewel encrusted with precious stones. He took it to a goldsmith to have it valued. The goldsmith's apprentice looked at it, sneakily removed the stones, told the boy it was worth three halfpence and that he would buy it. The boy said he would prefer the jewel back, so the apprentice gave it to him, but without the stones. The boy sued the goldsmith for his apprentice's attempt to cheat him. Lord Chief Justice Pratt ruled that even though the boy could not be said to own the jewel, he should be considered the rightful keeper ("finders keeper") until the original owner is found. In fact the apprentice and the boy both had a right of possession in the jewel (a technical concept, meaning evidence that something could belong to someone), but the boy's possessory interest was considered better, because it could be shown to be first in time. Possession may be nine tenths of the law, but not all.

This case is used to support the view of property in common law jurisdictions, that the person who can show the best claim to a piece of property, against any contesting party, is the owner. By contrast, the classic civil law approach to property, propounded by Friedrich Carl von Savigny, is that it is a right good against the world. Obligations, like contracts and torts are conceptualised as rights good between individuals.

The idea of property raises many further philosophical and political issues. Locke argued that our "lives, liberties and estates" are our property because we own our bodies and mix our labour with our surroundings.

Equity and trusts

Equity is a body of rules that developed in England separately from the "common law". The common law was administered by judges. The Lord Chancellor on the other hand, as the King's keeper of conscience, could overrule the judge made law if he thought it equitable to do so. This meant equity came to operate more through principles than rigid rules. For instance, whereas neither the common law nor civil law systems allow people to split the ownership from the control of one piece of property, equity allows this through an arrangement known as a 'trust'. 'Trustees' control property, whereas the 'beneficial' (or 'equitable') ownership of trust property is held by people known as 'beneficiaries'. Trustees owe duties to their beneficiaries to take good care of the entrusted property. In the early case of Keech v Sandford a child had inherited the lease on a market in Romford, London. Mr Sandford was entrusted to look after this property until the child matured. But before then, the lease expired. The landlord had (apparently) told Mr Sandford that he did not want the child to have the renewed lease. Yet the landlord was happy (apparently) to give Mr Sandford the opportunity of the lease instead. Mr Sandford took it. When the child (now Mr Keech) grew up, he sued Mr Sandford for the profit that he had been making by getting the market's lease. Mr Sandford was meant to be trusted, but he put himself in a position of conflict of interest. The Lord Chancellor, Lord King, agreed and ordered Mr Sandford should disgorge his profits. He wrote,

I very well see, if a trustee, on the refusal to renew, might have a lease to himself few trust-estates would be renewed ... This may seem very hard, that the trustee is the only person of all mankind who might not have the lease; but it is very proper that the rule should be strictly pursued and not at all relaxed.

Of course, Lord King LC was worried that trustees might exploit opportunities to use trust property for themselves instead of looking after it. Business speculators using trusts had just recently caused a stock market crash. Strict duties for trustees made their way into company law and were applied to directors and chief executive officers. Another example of a trustee's duty might be to invest property wisely or sell it.

This is especially the case for pension funds, the most important form of trust, where investors are trustees for people's savings until retirement. But trusts can also be set up for charitable purposes, famous examples being the British Museum or the Rockefeller Foundation.

Legal systems

In general, legal systems can be split between civil law and common law systems. The term "civil law" referring to a legal system should not be confused with "civil law" as a group of legal subjects distinct from criminal or public law. A third type of legal system—accepted by some countries without separation of church and state—is religious law, based on scriptures. The specific system that a country is ruled by is often determined by its history, connections with other countries, or its adherence to international standards. The sources that jurisdictions adopt as authoritatively binding are the defining features of any legal system. Yet classification is a matter of form rather than substance, since similar rules often prevail.

Civil law

Civil law is the legal system used in most countries around the world today. In civil law the sources recognised as authoritative are, primarily, legislation—especially codifications in constitutions or statutes passed by government—and custom. Codifications date back millennia, with one early example being the Babylonian Codex Hammurabi. Modern civil law systems essentially derive from the legal practice of the 6th-century Eastern Roman Empire whose texts were rediscovered by late medieval Western Europe. Roman law in the days of the Roman Republic and Empire was heavily procedural, and lacked a professional legal class. Instead a lay magistrate, iudex, was chosen to adjudicate. Precedents were not reported, so any case law that developed was disguised and almost unrecognised. Each case was to be decided afresh from the laws of the State, which mirrors the (theoretical) unimportance of judges' decisions for future cases in civil law systems today. From 529–534 AD the Byzantine Emperor Justinian I codified and consolidated Roman law up until that point, so that what remained was one-twentieth of the mass of legal texts from before. This became known as the Corpus Juris Civilis. As one legal historian wrote, "Justinian consciously looked back to the golden age of Roman law and aimed to restore it to the peak it had reached three centuries before." The Justinian Code remained in force in the East until the fall of the Byzantine Empire. Western Europe, meanwhile, relied on a mix of the Theodosian Code and Germanic customary law until the Justinian Code was rediscovered in the 11th century, and scholars at the University of Bologna used it to interpret their own laws. Civil law codifications based closely on Roman law, alongside some influences from religious laws such as Canon law, continued to spread throughout Europe until the Enlightenment; then, in the 19th century, both France, with the Code Civil, and Germany, with the Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch, modernised their legal codes. Both these codes influenced heavily not only the law systems of the countries in continental Europe (e.g. Greece), but also the Japanese and Korean legal traditions. Today, countries that have civil law systems range from Russia and China to most of Central and Latin America. The United States follows the common law system described below.

- Faculty of Literature and Philosophy

Literature (from Latin litterae (plural); letter) is the art of written work, and is not confined to published sources (although, under some circumstances, unpublished sources can also be exempt). The word literature literally means "acquaintance with letters" and the pars pro toto term "letters" is sometimes used to signify "literature," as in the figures of speech "arts and letters" and "man of letters." The four major classifications of literature are poetry, prose, fiction, and non-fiction.

Literature may comprise of texts based on factual information (journalistic or non-fiction), as well as on original imagination, such as polemical works as well as autobiography, and reflective essays as well as belles-lettres. Literatures can be divided according to historical periods, genres, and political influences. The concept of genre, which earlier was limited, has now broadened over the centuries. A genre consists of artistic works which fall within a certain central theme, and examples of genre include romance, mystery, crime, fantasy, erotica, and adventure, among others. Important historical periods include the 17th Century Shakespearean and Elizabethan times, Middle English, Old English, 19th Century Victorian, the Renaissance, the 18th Century Restoration, and 20th Century Modernism. Important political movements that have influenced literature include feminism, post-colonialism, psychoanalysis, post-structuralism, post-modernism, romanticism and Marxism. Literature is also observed in terms of gender, race and nationality, which include Black writing in America, African writing, Indian writing, Dalit writing, women's writing, and so on.

History

History of literature

The Epic of Gilgamesh is one of the earliest known literary works. This Babylonian epic poem arises from stories in the Sumerian language. Although the Sumerian stories are older (probably dating to at least 2100 B.C.), it was probably composed around 1900 BC. The epic deals with themes of heroism, friendship, loss, and the quest for eternal life.

Different historical periods are reflected in literature. National and tribal sagas, accounts of the origin of the world and of customs, and myths which sometimes carry moral or spiritual messages predominate in the pre-urban eras. The epics of Homer, dating from the early to middle Iron age, and the great Indian epics of a slightly later period, have more evidence of deliberate literary authorship, surviving like the older myths through oral tradition for long periods before being written down.

As a more urban culture developed, academies provided a means of transmission for speculative and philosophical literature in early civilizations, resulting in the prevalence of literature in Ancient China, Ancient India, Persia and Ancient Greece and Rome. Many works of earlier periods, even in narrative form, had a covert moral or didactic purpose, such as the Sanskrit Panchatantra or the Metamorphoses of Ovid. Drama and satire also developed as urban culture provided a larger public audience, and later readership, for literary production. Lyric poetry (as opposed to epic poetry) was often the speciality of courts and aristocratic circles, particularly in East Asia where songs were collected by the Chinese aristocracy as poems, the most notable being the Shijing or Book of Songs. Over a long period, the poetry of popular pre-literate balladry and song interpenetrated and eventually influenced poetry in the literary medium.

In ancient China, early literature was primarily focused on philosophy, historiography, military science, agriculture, and poetry. China, the origin of modern paper making and woodblock printing, produced one of the world's first print cultures. Much of Chinese literature originates with the Hundred Schools of Thought period that occurred during the Eastern Zhou Dynasty (770-256 BCE). The most important of these include the Classics of Confucianism, of Daoism, of Mohism, of Legalism, as well as works of military science (e.g. Sun Tzu's The Art of War) and Chinese history (e.g. Sima Qian's Records of the Grand Historian). Ancient Chinese literature had a heavy emphasis on historiography. The Chinese kept consistent and accurate court records after the year 841 BCE, with the beginning of the Gonghe regency of the Western Zhou Dynasty. An exemplary piece of narrative history of ancient China was the Zuo Zhuan, which was compiled no later than 389 BCE, and attributed to the blind 5th century BCE historian Zuo Qiuming.

In ancient India, literature originated from stories that were originally orally transmitted. Early genres included drama, fables, sutras and epic poetry. Sanskrit literature begins with the Vedas, dating back to 1500–1000 BCE, and continues with the Sanskrit Epics of Iron Age India. The Vedas are among the oldest sacred texts. The Samhitas (vedic collections) date to roughly 1500–1000 BCE, and the "circum-Vedic" texts, as well as the redaction of the Samhitas, date to c. 1000-500 BCE, resulting in a Vedic period, spanning the mid 2nd to mid 1st millennium BCE, or the Late Bronze Age and the Iron Age. The period between approximately the 6th to 1st centuries BC saw the composition and redaction of the two most influential Indian epics, the Mahabharata and the Ramayana, with subsequent redaction progressing down to the 4th century AD.

In ancient Greece, the epics of Homer, who wrote the Iliad and the Odyssey, and Hesiod, who wrote Works and Days and Theogony, are some of the earliest, and most influential, of Ancient Greek literature. Classical Greek genres included philosophy, poetry, historiography, comedies and dramas. Plato and Aristotle authored philosophical texts that are the foundation of Western philosophy, Sappho and Pindar were influential lyrical poets, and Herodotus and Thucydides were early Greek historians. Although drama was popular in Ancient Greece, of the hundreds of tragedies written and performed during the classical age, only a limited number of plays by three authors still exist: Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides. The plays of Aristophanes provide the only real examples of a genre of comic drama known as Old Comedy, the earliest form of Greek Comedy, and are in fact used to define the genre.

Roman histories and biographies anticipated the extensive mediaeval literature of lives of saints and miraculous chronicles, but the most characteristic form of the Middle Ages was the romance, an adventurous and sometimes magical narrative with strong popular appeal. Controversial, religious, political and instructional literature proliferated during the Renaissance as a result of the invention of printing, while the mediaeval romance developed into a more character-based and psychological form of narrative, the novel, of which early and important examples are the Chinese Monkey and the German Faust books.

In the Age of Reason philosophical tracts and speculations on history and human nature integrated literature with social and political developments. The inevitable reaction was the explosion of Romanticism in the later 18th century which reclaimed the imaginative and fantastical bias of old romances and folk-literature and asserted the primacy of individual experience and emotion. But as the 19th-century went on, European fiction evolved towards realism and naturalism, the meticulous documentation of real life and social trends. Much of the output of naturalism was implicitly polemical, and influenced social and political change, but 20th century fiction and drama moved back towards the subjective, emphasising unconscious motivations and social and environmental pressures on the individual. Writers such as Proust, Eliot, Joyce, Kafka and Pirandello exemplify the trend of documenting internal rather than external realities.

Genre fiction also showed it could question reality in its 20th century forms, in spite of its fixed formulas, through the enquiries of the skeptical detective and the alternative realities of science fiction. The separation of "mainstream" and "genre" forms (including journalism) continued to blur during the period up to our own times. William Burroughs, in his early works, and Hunter S. Thompson expanded documentary reporting into strong subjective statements after the second World War, and post-modern critics have disparaged the idea of objective realism in general.

Philosophy :

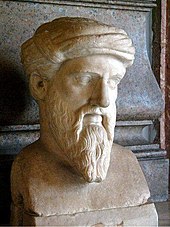

Philosophy is the study of general and fundamental problems, such as those connected with existence, knowledge, values, reason, mind, and language. Philosophy is distinguished from other ways of addressing such problems by its critical, generally systematic approach and its reliance on rational argument. The word "philosophy" comes from the Greek φιλοσοφία (philosophia), which literally means "love of wisdom".

Etymology

The introduction of the terms "philosopher" and "philosophy" has been ascribed to the Greek thinker Pythagoras. The ascription is said to be based on a passage in a lost work of Herakleides Pontikos, a disciple of Aristotle. It is considered to be part of the widespread body of legends of Pythagoras of this time. "Philosopher" was understood as a word which contrasted with "sophist" (from sophoi). Traveling sophists or "wise men" were important in Classical Greece, often earning money as teachers, whereas philosophers are "lovers of wisdom" and not professionals.

Branches of philosophy

Metaphilosophy :

The main areas of study in philosophy today include epistemology, logic, metaphysics, ethics and aesthetics.

Epistemology

Epistemology is concerned with the nature and scope of knowledge, such as the relationships between truth, belief, and theories of justification.

Skepticism is the position that questions the possibility of justifying any truth. Münchhausen Trilemma states that the three options to soundly prove any truth are not satisfactory. One is the regress argument where, by infinite regression, each proof requires a further proof. Infinitism claims that the chain can go forever. Another is foundationalism, where justification eventually rests on unproven basic beliefs or axioms. Logical atomism holds there are logical "facts" (or "atoms") that cannot be broken down any further. The other method of justification involves the circular argument, in which theory and proof support each other. Coherentism claims a belief is justified if it coheres with the larger belief system. More specifically, the coherence theory of truth states what is true is that which coheres with some specified set of propositions.

Rationalism is the emphasis on reasoning as a source of knowledge. Empiricism is the emphasis on observational evidence via sensory experience over other evidence as the source of knowledge. Rationalism claims that every possible object of knowledge can be deduced from coherent premises without observation. Empiricism claims that at least some knowledge is only a matter of observation. For this, Empiricism often cites the concept of tabula rasa, where individuals are not born with mental content and that knowledge builds from experience or perception. Epistemological solipsism is the idea that the existence of the world outside the mind is an unresolvable question.

Parmenides (fl. 500 BC) argued that it is impossible to doubt that thinking actually occurs. But thinking must have an object, therefore something beyond thinking really exists. Parmenides deduced that what really exists must have certain properties—for example, that it cannot come into existence or cease to exist, that it is a coherent whole, that it remains the same eternally (in fact, exists altogether outside time). This is known as the third man argument. Plato (427–347 BC) combined rationalism with a form of realism. The philosopher's work is to consider being, and the essence (ousia) of things. But the characteristic of essences is that they are universal. The nature of a man, a triangle, a tree, applies to all men, all triangles, all trees. Plato argued that these essences are mind-independent "forms", that humans (but particularly philosophers) can come to know by reason, and by ignoring the distractions of sense-perception.

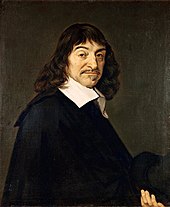

Modern rationalism begins with Descartes. Reflection on the nature of perceptual experience, as well as scientific discoveries in physiology and optics, led Descartes (and also Locke) to the view that we are directly aware of ideas, rather than objects. This view gave rise to three questions:

- Is an idea a true copy of the real thing that it represents? Sensation is not a direct interaction between bodily objects and our sense, but is a physiological process involving representation (for example, an image on the retina). Locke thought that a "secondary quality" such as a sensation of green could in no way resemble the arrangement of particles in matter that go to produce this sensation, although he thought that "primary qualities" such as shape, size, number, were really in objects.

- How can physical objects such as chairs and tables, or even physiological processes in the brain, give rise to mental items such as ideas? This is part of what became known as the mind-body problem.

- If all the contents of awareness are ideas, how can we know that anything exists apart from ideas?

Descartes tried to address the last problem by reason. He began, echoing Parmenides, with a principle that he thought could not coherently be denied: I think, therefore I am (often given in his original Latin: Cogito ergo sum). From this principle, Descartes went on to construct a complete system of knowledge (which involves proving the existence of God, using, among other means, a version of the ontological argument). His view that reason alone could yield substantial truths about reality strongly influenced those philosophers usually considered modern rationalists (such as Baruch Spinoza, Gottfried Leibniz, and Christian Wolff), while provoking criticism from other philosophers who have retrospectively come to be grouped together as empiricists.

Logic

Logic is the study of the principles of valid inference and correct reasoning. Today the subject of logic has two broad divisions: mathematical logic (formal symbolic logic) and what is now called philosophical logic. In deductive reasoning, an argument is constructed by showing a conclusion necessarily follows from a certain set of premises. Such an argument is called a syllogism. An argument is termed valid if its conclusion does indeed follow from its premises, whether the premises are true or not, while an argument is sound if its conclusion follows from premises that are true. Inferences from premises require rules of inference, such as the most popular method, modus ponens. Simple propositional logic involves inferences from propositions, which are declarations that are either true or false. Predicate logic deals with inferences from variables that need to be qualified by a quantifier as to when they are true and when they are false. Inductive reasoning makes conclusions or generalizations based on probabilistic reasoning.

Moral and political philosophy

Ethics and Political philosophy

Ethics or "moral philosophy", is concerned primarily with the question of the best way to live, and secondarily, concerning the question of whether this question can be answered. The main branches of ethics are meta-ethics, normative ethics, and applied ethics. Meta-ethics concerns the nature of ethical thought, such as the origins of the words good and bad, and origins of other comparative words of various ethical systems, whether there are absolute ethical truths, and how such truths could be known. Normative ethics are more concerned with the questions of how one ought to act, and what the right course of action is. This is where most ethical theories are generated. Lastly, applied ethics go beyond theory and step into real world ethical practice, such as questions of whether or not abortion is correct. Ethics is also associated with the idea of morality, and the two are often interchangeable.

One debate that has commanded the attention of ethicists in the modern era has been between consequentialism (actions are to be morally evaluated solely by their consequences) and deontology (actions are to be morally evaluated solely by consideration of agents' duties, the rights of those whom the action concerns, or both). Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill are famous for propagating utilitarianism, which is the idea that the fundamental moral rule is to strive toward the "greatest happiness for the greatest number". However, in promoting this idea they also necessarily promoted the broader doctrine of consequentialism. Adopting a position opposed to consequentialism, Immanuel Kant argued that moral principles were simply products of reason. Kant believed that the incorporation of consequences into moral deliberation was a deep mistake, since it denies the necessity of practical maxims in governing the working of the will. According to Kant, reason requires that we conform our actions to the categorical imperative, which is an absolute duty. An important 20th-century deontologist, W.D. Ross, argued for weaker forms of duties called prima facie duties.

More recent works have emphasized the role of character in ethics, a movement known as the aretaic turn (that is, the turn towards virtues). One strain of this movement followed the work of Bernard Williams. Williams noted that rigid forms of consequentialism and deontology demanded that people behave impartially. This, Williams argued, requires that people abandon their personal projects, and hence their personal integrity, in order to be considered moral. G.E.M. Anscombe, in an influential paper, "Modern Moral Philosophy" (1958), revived virtue ethics as an alternative to what was seen as the entrenched positions of Kantianism and consequentialism. Aretaic perspectives have been inspired in part by research of ancient conceptions of virtue. For example, Aristotle's ethics demands that people follow the Aristotelian mean, or balance between two vices; and Confucian ethics argues that virtue consists largely in striving for harmony with other people. Virtue ethics in general has since gained many adherents, and has been defended by such philosophers as Philippa Foot, Alasdair MacIntyre, and Rosalind Hursthouse.

Political philosophy is the study of government and the relationship of individuals (or families and clans) to communities including the state. It includes questions about justice, law, property, and the rights and obligations of the citizen. Politics and ethics are traditionally inter-linked subjects, as both discuss the question of what is good and how people should live. From ancient times, and well beyond them, the roots of justification for political authority were inescapably tied to outlooks on human nature. In The Republic, Plato presented the argument that the ideal society would be run by a council of philosopher-kings, since those best at philosophy are best able to realize the good. Even Plato, however, required philosophers to make their way in the world for many years before beginning their rule at the age of fifty. For Aristotle, humans are political animals (i.e. social animals), and governments are set up to pursue good for the community. Aristotle reasoned that, since the state (polis) was the highest form of community, it has the purpose of pursuing the highest good. Aristotle viewed political power as the result of natural inequalities in skill and virtue. Because of these differences, he favored an aristocracy of the able and virtuous. For Aristotle, the person cannot be complete unless he or she lives in a community. His The Nicomachean Ethics and The Politics are meant to be read in that order. The first book addresses virtues (or "excellences") in the person as a citizen; the second addresses the proper form of government to ensure that citizens will be virtuous, and therefore complete. Both books deal with the essential role of justice in civic life.

Nicolas of Cusa rekindled Platonic thought in the early 15th century. He promoted democracy in Medieval Europe, both in his writings and in his organization of the Council of Florence. Unlike Aristotle and the Hobbesian tradition to follow, Cusa saw human beings as equal and divine (that is, made in God's image), so democracy would be the only just form of government. Cusa's views are credited by some as sparking the Italian Renaissance, which gave rise to the notion of "Nation-States".

Later, Niccolò Machiavelli rejected the views of Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas as unrealistic. The ideal sovereign is not the embodiment of the moral virtues; rather the sovereign does whatever is successful and necessary, rather than what is morally praiseworthy. Thomas Hobbes also contested many elements of Aristotle's views. For Hobbes, human nature is essentially anti-social: people are essentially egoistic, and this egoism makes life difficult in the natural state of things. Moreover, Hobbes argued, though people may have natural inequalities, these are trivial, since no particular talents or virtues that people may have will make them safe from harm inflicted by others. For these reasons, Hobbes concluded that the state arises from a common agreement to raise the community out of the state of nature. This can only be done by the establishment of a sovereign, in which (or whom) is vested complete control over the community, and is able to inspire awe and terror in its subjects.

Many in the Enlightenment were unsatisfied with existing doctrines in political philosophy, which seemed to marginalize or neglect the possibility of a democratic state. Jean-Jacques Rousseau was among those who attempted to overturn these doctrines: he responded to Hobbes by claiming that a human is by nature a kind of "noble savage", and that society and social contracts corrupt this nature. Another critic was John Locke. In Second Treatise on Government he agreed with Hobbes that the nation-state was an efficient tool for raising humanity out of a deplorable state, but he argued that the sovereign might become an abominable institution compared to the relatively benign unmodulated state of nature.

Following the doctrine of the fact-value distinction, due in part to the influence of David Hume and his student Adam Smith, appeals to human nature for political justification were weakened. Nevertheless, many political philosophers, especially moral realists, still make use of some essential human nature as a basis for their arguments.

Marxism is derived from the work of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Their idea that capitalism is based on exploitation of workers and causes alienation of people from their human nature, the historical materialism, their view of social classes, etc., have influenced many fields of study, such as sociology, economics, and politics. Marxism inspired the Marxist school of communism, which brought a huge impact on the history of the 20th century.

- Faculty of Mathematics, Physics and Natural Sciences

Mathematics (from Greek μάθημα máthēma, “knowledge, study, learning”) is the study of quantity, structure, space, and change. Mathematicians seek out patterns and formulate new conjectures. Mathematicians resolve the truth or falsity of conjectures by mathematical proof. The research required to solve mathematical problems can take years or even centuries of sustained inquiry. Since the pioneering work of Giuseppe Peano (1858–1932), David Hilbert (1862–1943), and others on axiomatic systems in the late 19th century, it has become customary to view mathematical research as establishing truth by rigorous deduction from appropriately chosen axioms and definitions. When those mathematical structures are good models of real phenomena, then mathematical reasoning often provides insight or predictions.

Through the use of abstraction and logical reasoning, mathematics developed from counting, calculation, measurement, and the systematic study of the shapes and motions of physical objects. Practical mathematics has been a human activity for as far back as written records exist. Rigorous arguments first appeared in Greek mathematics, most notably in Euclid's Elements. Mathematics developed at a relatively slow pace until the Renaissance, when mathematical innovations interacting with new scientific discoveries led to a rapid increase in the rate of mathematical discovery that continues to the present day.

Galileo Galilei (1564–1642) said, 'The universe cannot be read until we have learned the language and become familiar with the characters in which it is written. It is written in mathematical language, and the letters are triangles, circles and other geometrical figures, without which means it is humanly impossible to comprehend a single word. Without these, one is wandering about in a dark labyrinth'. Carl Friedrich Gauss (1777–1855) referred to mathematics as "the Queen of the Sciences". Benjamin Peirce (1809–1880) called mathematics "the science that draws necessary conclusions". David Hilbert said of mathematics: "We are not speaking here of arbitrariness in any sense. Mathematics is not like a game whose tasks are determined by arbitrarily stipulated rules. Rather, it is a conceptual system possessing internal necessity that can only be so and by no means otherwise." Albert Einstein (1879–1955) stated that "as far as the laws of mathematics refer to reality, they are not certain; and as far as they are certain, they do not refer to reality".

Mathematics is used throughout the world as an essential tool in many fields, including natural science, engineering, medicine, and the social sciences. Applied mathematics, the branch of mathematics concerned with application of mathematical knowledge to other fields, inspires and makes use of new mathematical discoveries and sometimes leads to the development of entirely new mathematical disciplines, such as statistics and game theory. Mathematicians also engage in pure mathematics, or mathematics for its own sake, without having any application in mind. There is no clear line separating pure and applied mathematics, and practical applications for what began as pure mathematics are often discovered.

History

History of mathematics

The evolution of mathematics might be seen as an ever-increasing series of abstractions, or alternatively an expansion of subject matter. The first abstraction, which is shared by many animals, was probably that of numbers: the realization that a collection of two apples and a collection of two oranges (for example) have something in common, namely quantity of their members.

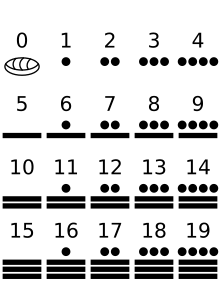

In addition to recognizing how to count physical objects, prehistoric peoples also recognized how to count abstract quantities, like time – days, seasons, years. Elementary arithmetic (addition, subtraction, multiplication and division) naturally followed.

Since numeracy pre-dated writing, further steps were needed for recording numbers such as tallies or the knotted strings called quipu used by the Inca to store numerical data. Numeral systems have been many and diverse, with the first known written numerals created by Egyptians in Middle Kingdom texts such as the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus.

The earliest uses of mathematics were in trading, land measurement, painting and weaving patterns and the recording of time. More complex mathematics did not appear until around 3000 BC, when the Babylonians and Egyptians began using arithmetic, algebra and geometry for taxation and other financial calculations, for building and construction, and for astronomy. The systematic study of mathematics in its own right began with the Ancient Greeks between 600 and 300 BC.

Mathematics has since been greatly extended, and there has been a fruitful interaction between mathematics and science, to the benefit of both. Mathematical discoveries continue to be made today. According to Mikhail B. Sevryuk, in the January 2006 issue of the Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society, "The number of papers and books included in the Mathematical Reviews database since 1940 (the first year of operation of MR) is now more than 1.9 million, and more than 75 thousand items are added to the database each year. The overwhelming majority of works in this ocean contain new mathematical theorems and their proofs."

Inspiration, pure and applied mathematics, and aesthetics

Mathematics arises from many different kinds of problems. At first these were found in commerce, land measurement, architecture and later astronomy; nowadays, all sciences suggest problems studied by mathematicians, and many problems arise within mathematics itself. For example, the physicist Richard Feynman invented the path integral formulation of quantum mechanics using a combination of mathematical reasoning and physical insight, and today's string theory, a still-developing scientific theory which attempts to unify the four fundamental forces of nature, continues to inspire new mathematics. Some mathematics is only relevant in the area that inspired it, and is applied to solve further problems in that area. But often mathematics inspired by one area proves useful in many areas, and joins the general stock of mathematical concepts. A distinction is often made between pure mathematics and applied mathematics. However pure mathematics topics often turn out to have applications, e.g. number theory in cryptography. This remarkable fact that even the "purest" mathematics often turns out to have practical applications is what Eugene Wigner has called "the unreasonable effectiveness of mathematics". As in most areas of study, the explosion of knowledge in the scientific age has led to specialization: there are now hundreds of specialized areas in mathematics and the latest Mathematics Subject Classification runs to 46 pages. Several areas of applied mathematics have merged with related traditions outside of mathematics and become disciplines in their own right, including statistics, operations research, and computer science.

For those who are mathematically inclined, there is often a definite aesthetic aspect to much of mathematics. Many mathematicians talk about the elegance of mathematics, its intrinsic aesthetics and inner beauty. Simplicity and generality are valued. There is beauty in a simple and elegant proof, such as Euclid's proof that there are infinitely many prime numbers, and in an elegant numerical method that speeds calculation, such as the fast Fourier transform. G. H. Hardy in A Mathematician's Apology expressed the belief that these aesthetic considerations are, in themselves, sufficient to justify the study of pure mathematics. He identified criteria such as significance, unexpectedness, inevitability, and economy as factors that contribute to a mathematical aesthetic. Mathematicians often strive to find proofs that are particularly elegant, proofs from "The Book" of God according to Paul Erdős. The popularity of recreational mathematics is another sign of the pleasure many find in solving mathematical questions.

Physics :

Physics (from Greek: φύσις physis "nature") is a natural science that involves the study of matter and its motion through spacetime, along with related concepts such as energy and force. More broadly, it is the general analysis of nature, conducted in order to understand how the universe behaves.

Physics is one of the oldest academic disciplines, perhaps the oldest through its inclusion of astronomy.

Over the last two millennia, physics was a part of natural philosophy along with chemistry, certain branches of mathematics, and biology, but during the Scientific Revolution in the 16th century, the natural sciences emerged as unique research programs in their own right. Physics intersects with many interdisciplinary areas of research, such as biophysics and quantum chemistry, and the boundaries of physics are not rigidly defined. New ideas in physics often explain the fundamental mechanisms of other sciences, while opening new avenues of research in areas such as mathematics and philosophy.

Physics also makes significant contributions through advances in new technologies that arise from theoretical breakthroughs. For example, advances in the understanding of electromagnetism or nuclear physics led directly to the development of new products which have dramatically transformed modern-day society, such as television, computers, domestic appliances, and nuclear weapons; advances in thermodynamics led to the development of industrialization; and advances in mechanics inspired the development of calculus.

History

Main article: History of physics

As noted below, the means used to understand the behavior of natural phenomena and their effects evolved from philosophy, progressively replaced by natural philosophy then natural science, to eventually arrive at the modern conception of physics.

Natural philosophy has its origins in Greece during the Archaic period, (650 BCE – 480 BCE), when Pre-Socratic philosophers like Thales refused supernatural, religious or mythological explanations for natural phenomena and proclaimed that every event had a natural cause. They proposed ideas verified by reason and observation and many of their hypotheses proved successful in experiment, for example atomism.

Natural science was developed in China, India and in Islamic caliphates, between the 4th and 10th century BCE. Quantitative descriptions became popular among physicists and astronomers, for example Archimedes in the domains of mechanics, statics and hydrostatics. Experimental physics had its debuts with experimentation concerning statics by medieval Muslim physicists like al-Biruni and Alhazen.

Classical physics became a separate science when early modern Europeans used these experimental and quantitative methods to discover what are now considered to be the laws of physics. Kepler, Galileo and more specifically Newton discovered and unified the different laws of motion. During the industrial revolution, as energy needs increased, so did research, which led to the discovery of new laws in thermodynamics, chemistry and electromagnetics.

Modern physics started with the works of Einstein both in relativity and quantum physics.

Philosophy

For more details on this topic, see Philosophy of physics.